- Agnieszka Polak,

- Grzegorz Machnik,

- Łukasz Bułdak,

- Weronika Wójtowicz,

- Jarosław Ruczyński,

- Katarzyna Prochera,

- Piotr Mucha,

- Piotr Rekowski &

- Bogusław Okopień

- 341 Accesses

- Explore all metrics

Abstract

Purpose

Peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) are synthetic molecules with a unique N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine backbone that offer increased stability and resistance to degradation compared to DNA/RNA. The ability of these compounds to bind complementarily to DNA or RNA, forming various stable hybrids, makes them hold potential for applications in gene therapy and molecular diagnostics. Nonetheless, the poor ability of PNAs to cross cell membranes required the use of delivery systems. This study aimed to establish and optimize non-covalent PNA, and cell penetrating peptide (CPP) complexes and evaluate their efficiency thereby establishing a tool for future targeted therapeutic applications.

Methods

This study utilized three different CPPs to deliver PNA, demonstrating successful cell membrane crossing in vitro. We optimized PNA and CPP concentrations and evaluated the efficiency of the CPPs. The CPPs used were TP10, Tat, and TD2.2. The PNAs and CPPs were complexed via non-covalent binding. Each CPP molecule was designed to contain a nuclear localization signal (NLS) fragment at their 3’ end to enhance nuclear delivery. Research methods included cellular fluorescence measurement, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, western blot, and cell viability assessment using the MTT assay.

Results

We optimized PNA and CPP concentrations and evaluated the efficiency of the CPPs, finding that TP10 was more effective in comparison with TD2.2 and Tat. This approach effectively delivered PNAs to their specific location.

Conclusion

The obtained results demonstrated the effective delivery of PNAs combined with CPPs to their specific cellular location thus suggesting that this may pose a promising strategy for analogous targeted molecular applications.

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, books and news in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.

- Nucleotide-binding proteins

- Peptide

- Peptide Delivery

- Protein Delivery

- Recombinant Peptide Therapy

- Peptide nucleic acid oligo

Introduction

Peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) are artificially designed molecules characterized by a backbone composed of N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine (Suparpprom and Vilaivan 2022). Unlike natural nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA, PNAs lack a negatively charged phosphate backbone (Montazersaheb et al. 2018). This results in the absence of electrostatic repulsion between PNA-PNA, as well as PNA-DNA and PNA-RNA hybrids, leading to greater stability of these complexes (Pellestor and Paulasova 2004; Gupta et al. 2017). This structural modification endows PNAs with unique properties such as increased stability, reduced nonspecific interactions, and resistance to enzymatic degradation (Machnik et al. 2014). Owing to these features, PNAs hold great potential for use in various fields of biology and medicine, including gene therapy, molecular diagnostics, and antisense therapy. Thanks to the nucleobase composition of PNA, this molecule can complementarily bind to both DNA and RNA. However, unlike naturally occurring nucleic acids, PNA-DNA hybrids can form different binding modes, such as duplexes, triplexes, or duplex invasions of triplexes (Berillo et al. 2021).

The high binding stability and efficiency, together with the low toxicity of PNAs, indicate their significant potential as a tool for modulating gene expression. However, the limited ability of PNAs to penetrate cell membranes poses a significant barrier to their practical application. Consequently, to develop effective therapeutic agents, these limitations must be overcome. To increase the efficiency of PNA delivery to cells, various strategies are frequently employed, such as conjugation with DNA oligomers, PNA receptor ligands, or cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs). In particular, the conjugation of PNAs with CPPs is a promising strategy that can significantly increase the efficiency of PNA delivery to (specific types of) cells and facilitate their broad application in research and therapy (Singh et al. 2018).

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) are short sequences of amino acids that, owing their positive electrical charge, can effectively penetrate cell membranes and simultaneously deliver various cargoes, such as drugs or nucleic acids, into the cell interior (Gori et al. 2023). Certain CPPs are able to specifically interact with target cells, demonstrating strong efficiency even at low, biologically acceptable concentrations. The use of CPPs allows for the introduction of larger molecules that would normally be unable to enter the cell (Patel et al. 2019). A key characteristic of certain CPPs is not only their capacity to penetrate the cell membrane but also their ability to target specific organelles, thereby further increasing the precision of delivery. Combining CPPs with a therapeutic molecule results in greater control over drug delivery and simultaneously reduces side effects on other cell types. The mechanism of action of CPPs involves their ability to form complexes with transported molecules, which are then absorbed by the cell (Bottens and Yamada 2022). Importantly, covalent binding between a CPP and the transported molecule is not needed; transport efficiency depends on various factors, such as the molar ratio of CPP to the transported molecule and environmental conditions. The efficiency of CPPs themselves is influenced by numerous factors, including amino acid composition, sequence length, charge, hydrophobicity, and stability (Ramsey and Flynn 2015). A positive charge facilitates interactions with negatively charged cell membranes (Lehto et al. 2016). Hydrophobic interactions are an important issue (Ruseska and Zimmer 2023). Excessive hydrophobicity can lead to peptide aggregation, whereas insufficient hydrophobicity can limit the ability of CPPs to pass through the membrane. Additionally, CPPs need to be resistant to enzymatic degradation and should demonstrate appropriate cell specificity to effectively deliver their cargo to target cells.

In previous studies, we characterized the effects of PNAs on transcription and translation processes in vitro via cell-free systems. On the basis of the obtained results, we selected the most effective PNA design and optimized its concentration. The aim of those studies was to investigate the effectiveness of selected PNAs in modulating gene expression in a cell-free environment. Currently, we are focusing on the next step of potential therapeutic usage of PNAs, which includes their delivery in a cellular setting.

To deliver PNA to the cell nucleus, we employed a two-pronged strategy. First, we utilized PNAs conjugated with cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) that facilitated the passage of these molecules through the cell membrane (Saarbach et al. 2019). Second, we incorporated a nuclear localization signal (NLS) at the C-terminus of the PNA sequence. The NLS is composed of several basic amino acids that function by directing proteins toward the cell nucleus. Consequently, upon entering the cell, PNAs are actively transported to the nucleus, where they can eventually bind to their target DNA sequences and modulate gene expression via antisense mechanisms.

Based on our previous research, we designed and selected optimal PNA molecules. In subsequent experiments, we utilized PNAs complementary to ACLY (ATP citrate lyase) and PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9). Both oligomers incorporated a nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequence at their C-terminus to facilitate efficient delivery of these molecules to the cell nucleus (Katzmann et al. 2020). ACLY is a key enzyme in fatty acid synthesis. Like the therapeutic application of PCSK9 inhibitors, ACLY is a target gene in the development of drugs against hypercholesterolemia. Inhibition of ACLY activity leads to a decrease in acetyl-CoA production, subsequently inhibiting fatty acid synthesis. Since cholesterol is synthesized from the same precursors as fatty acids, ACLY inhibition eventually results in a reduction in blood cholesterol levels. This also affects the regulation of additional genes participating in lipid metabolism, potentially leading to a further decrease in cholesterol levels (Hajar 2019; Liu et al. 2022). PCSK9 plays a key role in the metabolic processing of low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) (Peterson et al. 2008; Yurtseven et al. 2020; Seidah et al. 2017). The LDL receptor is responsible for capturing LDL cholesterol from the blood and transporting it into liver cells, where it is degraded (Lee et al. 2023). Inhibition of PCSK9 increases the abundance of LDL receptors on hepatocyte membranes, allowing the liver to capture LDL-C from the bloodstream more effectively, thereby reducing its level and mitigating the risk of cardiovascular disease (Abifadel et al. 2003).

Materials and Methods

Reagents

All chemicals and solvents used were of analytical, HPLC, or LC–MS grade. Solutions were freshly made with distilled and deionized water obtained from a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), and filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane prior to use. The Fmoc-XAL-PEG-PS resin employed for PNA synthesis was sourced from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Fmoc/Bhoc (fluorenyl-9-methoxycarbonyl/benzhydryloxycarbonyl) protected PNA monomers were purchased from Panagene (Billingham, Cleveland, United Kingdom). Fmoc-Arg(Boc)2-OH, Fmoc-Ahx (6-Fmoc-aminohexanoic acid), and Fmoc-Aha (4-azidohomoalanine) were obtained from Iris Biotech GmbH (Marktredwitz, Germany). The Fmoc-protected amino acids used for peptide synthesis were purchased from Bachem AG (Bublendorf, Switzerland). NHS-fluorescein (5/6-carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Additional chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (Poznań, Poland).

Synthesis of Fluo-PNA-Ahx-NLS Conjugates

The conjugate of fluorescein-labeled PNA with Ahx-NLS (working name: Fluo-PCSK9-PPT-EX1-Ahx-NLS) was synthesized using solid-phase synthesis (SPS) on an automatic peptide synthesizer (Quartet, Protein Technologies, Tucson, AZ, USA) following the Fmoc chemistry. It’s sequence was as follows: Fluo-A-G-A-G-G-A-G-G-A-A-G-Ahx-Pro-Lys-Lys-Lys-Arg-Lys-Val-amide (calculated MW = 4477.62). The detailed working procedure for obtaining and purification of PNA-conjugates was described in Polak et al. (2024). Eventually, synthesized compounds were identified by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI–MS, Shimadzu LCMS-2020). The physicochemical properties of synthesized compounds, including their calculated molecular weights, observed ions ([m/z]), and yields are presented in Table 2.

Synthesis of Cell-Penetrating Peptides

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) were synthesized by the solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) with the use of automatic peptide synthesizer (Quartet, Protein Technologies) and Fmoc (fluorenyl-9-methoxycarbonyl) strategy (Wender et al. 2000). CPPs compositions are listed in Table 1. Whole synthesis- as well as purification procedures were previously described in details in Ruczyński et al. (2024). The HPLC purity of the peptides was established to be greater than 95%, and the molecular mass of the synthesized compounds was confirmed by mass spectrometry (Table 2).Table 1 Sequences of cell-penetrating peptides used in experiment

Full size tableTable 2 The physicochemical properties of synthesized compounds, including their calculated molecular weights, observed ions ([m/z]), and yields

Prior to commencing detailed experiments with specific molecules, preliminary optimization studies were conducted. These involved testing various cell lines, as well as diverse PNA (Peptide Nucleic Acid) and CPP (Cell-Penetrating Peptide) molecules at different concentrations. The cell lines evaluated included: U87MG, NHA, HepG2, CHO-K1, HEK293T, and HeLa. Among these, HeLa and HEK293T cells proved to be the most optimal for further investigation.

For method optimization, the following CPP molecules were utilized at varying concentrations: Transportan 10 (TP10), Prop-Tat(47–57) (Tat), and TD2.2-Aha. Of those tested, the TP10 molecule demonstrated the highest efficiency and was consequently selected for subsequent research phases.

The PNA molecules employed were: Fluo-ACLY-INIT-Ahx-NLS (Fluo-A-C-C-G-G-C-T-G-C-T-G-G-G-G-T-Ahx-Pro-Lys-Lys-Lys-Arg-Lys-Val-amide), Fluo-PCSK9-INIT-Ahx-NLS (Fluo-G-G-A-T-C-G-T-C-C-G-A-T-G-G-G-Ahx-Pro-Lys-Lys-Lys-Arg-Lys-Val-amide), Fluo-PCSK9-PPT-EX1-Ahx-NLS (Fluo-A-G-A-G-G-A-G-G-A-A-G-Ahx-Pro-Lys-Lys-Lys-Arg-Lys-Val-amide), and Fluo-PCSK9-EX2-Ahx-NLS (Fluo-G-A-G-G-A-G-G-A-C-T-C-C-T-C-T-Ahx-Pro-Lys-Lys-Lys-Arg-Lys-Val-amide). These had been previously used in cell-free experiments. In the current study phase, previously obtained results were confirmed, unequivocally identifying Fluo-PCSK9-PPT-EX1-Ahx-NLS as the most suitable molecule for further analysis.

Cell Culture

Experiments were conducted on several different cell lines: CHO-K1 (ATCC: CCL-61), HeLa (ATCC: CCL-2), HEK293T (ATCC: CRL-3216), and U-87MG (ATCC: HTB-14). The most efficient results were obtained using the HEK293T and HeLa cell lines. These two cell lines presented the highest transfection efficiency and yielded the best initial results and were therefore further developed in subsequent stages of the study. To evaluate the effectiveness of the CPP and PNA mixtures, HeLa and HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM medium from Capricorn Scientific (Ebsdorfergrund, GmbH), supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% antibiotics, and 1% L-glutamine. The cells were passaged on 10 mm-diameter culture dishes and subsequently transferred to 12- and 96-well plates. On the day of the experiment, the cells reached approximately 80% confluence.

Stock solutions were prepared by dissolving lyophilized CPP and fluoPNA in water to create 100 mM and 10 mM solutions, respectively. The FluoPNA and CPP solutions were mixed at an appropriate ratio in OPTI-Mem transfection medium. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature (RT) for 30 min and then added to the culture medium. Based on preliminary research findings, CPP TP10 and PNA with the sequence Fluo-PCSK9-PPT-EX1-Ahx-NLS were selected because of their optimal efficiency. In this study, cell groups treated with 80 pmol PNA, 60 pmol CPP, 80 pmol PNA in combination with 60 pmol CPP, and untreated control cells were utilized. The cells were left with these mixtures and incubated for 3 h. The cells incubated in OPTI-Mem medium without the addition of CPP or fluoPNA served as negative controls, and the cells incubated in medium with CPP alone or fluoPNA alone served as single-compound controls.

After incubation with the CPP with the PNA mixture (CPP TP10 and PNA with the sequence Fluo-PCSK9-PPT-EX1-Ahx-NLS), the cell condition was assessed via a Delta Optical IB-100 inverted microscope (Delta Optical, Mińsk Mazowiecki, Poland) with a fluorescent attachment. Fluorescence microscopy was used to visualize fluorescence changes directly in cells from particular groups. Overall cell fluorescence was subsequently analyzed via a Synergy H1 Microplate Reader (BioTek).

Fluorescence Measurement on In Vitro Culture Plates

To analyze the fluorescence of cells after incubation with the test substances (CPP and fluoPNA), HeLa and HEK293T cells were seeded and cultivated in a 96-well plate. Based on preliminary research findings, CPP TP10 and PNA with the sequence Fluo-PCSK9-PPT-EX1-Ahx-NLS were selected due to their optimal efficiency. In this study, cell groups treated with 6.7 pmol PNA, 5.1 pmol CPP, or 6.7 pmol PNA in combination with 5.1 pmol CPP, and untreated control cells were utilized.

Upon completion of the experiment, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed once with PBS buffer to remove any growth medium and unattached cells. Following gentle tapping of the plate to remove residual liquid, fluorescence was measured without delay using a microplate reader. The measurements were performed with a BioTek Synergy H1 reader (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). An appropriate measurement protocol was selected, with a fixed excitation wavelength of 465 nm and different emission wavelengths at 495, 500, 510, and 520 nm. All the obtained data were then transferred to an Excel spreadsheet, where the average fluorescence for each cell group was calculated at a chosen emission wavelength. Thereafter, a comparison between groups was performed. Based on the obtained data, graphs and tables presenting the results were generated. CPP (TP10) combined with PNA with the sequence Fluo-PCSK9-PPT-EX1-Ahx-NLS was used for the study. Each experimental condition was repeated three times.

High-Performance Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was also employed to analyze the cell extracts, utilizing the fluorescence properties of fluoPNA molecules. These initial investigations provided valuable insights into component separation and retention times, serving as a crucial foundational step for more extensive, future studies. The analysis was performed on HeLa cell lines. Based on preliminary research findings, CPP TP10 and PNA with the sequence Fluo-PCSK9-PPT-EX1-Ahx-NLS were selected due to their optimal efficiency.

The cells were harvested directly from the culture wells of a 12-well plate with 200 µL of RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Warsaw, Poland). Before lysis, the cells were washed with cold PBS. The cell lysates were then sonicated via a VibraCell (Sonics) to disrupt the cell membranes and maximize the release of fluorescein-labeled fluoPNA. After sonication, the cell extracts were divided into two aliquots; one part was stored at − 80 °C for Western blot analysis, while the other was further processed by filtration using a Spartan 13/0.45 RC (Whatman, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA) syringe filter and subjected to HPLC processing.

The relative amount of fluoPNA molecules and by extension, the transfection efficiency was assessed via reverse-phase HPLC coupled with fluorescence detection. Sample separation was performed on a Merck/Hitachi D-7000 HPLC system equipped with a Hitachi/Merck LaChrom L-7485 fluorescence detector. A Phenomenex Kinetex C18 reversed-phase column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 2.6 µm particle size; Shim-Pol, Warsaw, Poland; cat. no. 00F-4462-E0) was used for chromatographic separation. Elution was carried out using a gradient of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in deionized water (Solvent A) and 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile (Solvent B), shifting from 45%A/65%B to 40%A/60%B over a 20 min period. Both water and acetonitrile (HPLC gradient grade) were obtained from Linegal Chemicals (Warsaw, Poland), while TFA was sourced from Merck Millipore (Poznań, Poland).

Western Blot

Upon completion of cell culture, the cells from the 12-well plate were collected and resuspended in 200 µL of RIPA buffer, as described previously in the “High-performance pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis” selection. The cell samples were removed from − 80 °C storage and thawed on ice. Then, 2.5 µL of Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Warsaw, Poland) was added. An aliquot of 15 µL of sample was mixed with 15 µL of Novex Tris–Glycine SDS Sample Buffer (2X) (Thermo Scientific, Warsaw, Poland) and denatured at 96 °C for 6 min and placed on ice for 3 min. A total amount of 10 µg of protein sample was then loaded onto a 10% polyacrylamide (PAA) denaturing gel. For comparative purposes, a broad-range protein size marker (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) was loaded onto the gel. Following electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto an Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (Merck Millipore, Poznań, Poland) by electroblotting at 100 mA overnight. The next day, the membrane was rinsed with TTBS and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue to reveal the protein bands. (Coomassie Brilliant Blue R 250, Merck, Poznań, Poland). Irreversible protein staining of the PVDF membrane was performed following the protocol by Pryor et al. Each experimental condition was repeated three times. After drying, the membranes were scanned and visible protein bands were analyzed via ImageJ software (Schindelin et al. 2012).

Cell Viability Assessment Using the MTT Assay

Cell viability of cell lines (HEK293T and HeLA) treated with previously optimized PNA/CPP/PNA + CPP concentration was assessed. Cells were seeded on a 12-well plate and previously treated with medium, PNA, CPP, and PNA + CPP was estimated using the colorimetric MTT assay (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, Sigma-Aldrich Co. (Poznań, Poland). Each experimental condition was conducted in triplicate (n = 3).

Cells were incubated for 24 h under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO₂). After incubation with the tested compounds, the medium was removed, and cells were washed once with PBS buffer from Capricorn Scientific (Ebsdorfergrund, GmbH). A fresh MTT solution (in PBS buffer) was added to each well to reach a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. After incubation, the MTT solution was removed, and DMSO from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (Poznań, Poland) was added to the wells. The plates were then incubated for 30 min at 37 °C to dissolve the formazan crystals.

Absorbance was measured using a microplate reader xMark Microplate Spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at a wavelength of 570 nm, with a reference wavelength of 620 nm to subtract background absorbance.

Cell viability (% of viable cells) was calculated based on the average absorbance from replicates using the following formula:

Statistical Analysis

The data were initially organized using Microsoft Excel (v. 1808, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and then imported into Statistica software (version 13.0, StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) and the Plus Set (version 5.0, TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) for analysis. The normality of variable distributions was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Statistical comparisons were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. The results are presented as the mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

The experimental conditions employed in the study were based on results from previous experiments, in which the research setting was optimized (Polak et al. 2024). At the beginning of the experiments, we compared the efficiency of PNA transport into cells using different cell-penetrating peptides, such as TD2.2, Tat, and TP10. Preliminary results revealed that the TP10 peptide provided the most effective PNA transport, despite earlier reports indicating the greater versatility of TD2.2 and Tat.

Our experimental results demonstrated that this approach significantly increased PNA accumulation within the nucleus, confirming the effectiveness of this strategy for delivering PNAs to their target site of action.

Cell Culture and Fluorescence Microscopy Analysis

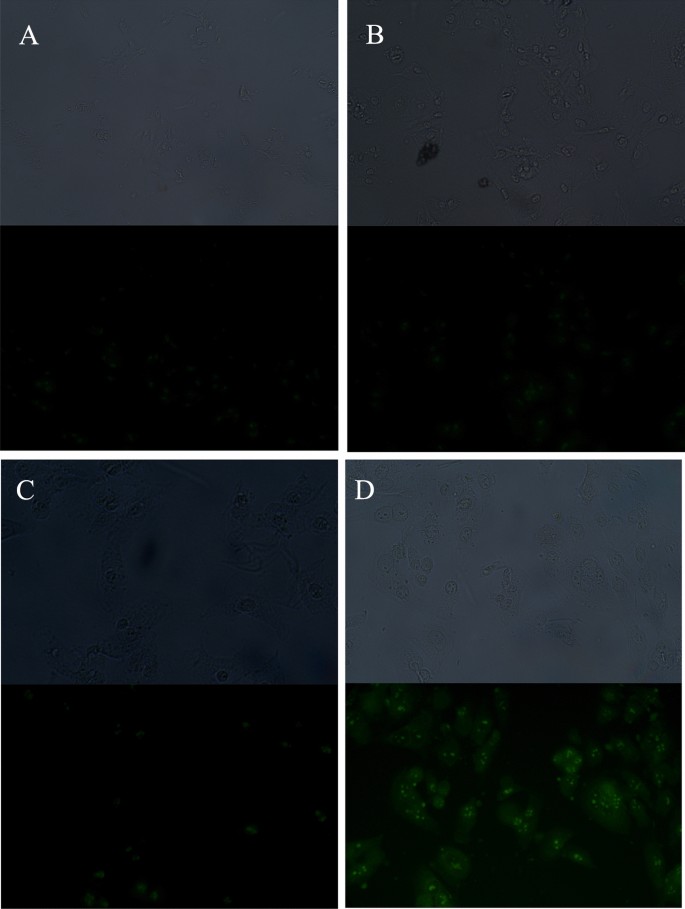

The use of CPPs significantly increased the internalization of fluorescein-labeled PNA (fluoPNA) into HeLa cells, as confirmed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1). The results revealed that cells incubated with fluoPNAs in the presence of CPP exhibited significantly stronger fluoPNA-derived fluorescence in comparison with control cells or cells incubated solely with fluoPNAs or CPPs. These results indicated that the CPPs facilitated the transport of fluoPNAs across the cell membrane, enabling their efficient penetration into the cells.

The Measurement of Fluorescence Intensity Using Plate Reader

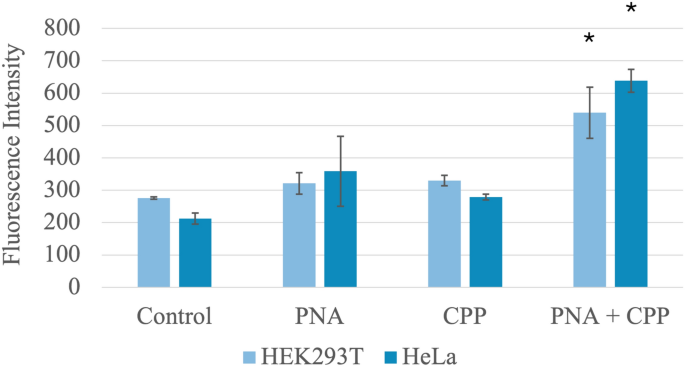

Quantitative analysis of the data obtained from the plate reader statistically confirmed the increase in fluoPNA internalization previously observed via fluorescence microscopy. HeLa and 293 T cells incubated with fluoPNA and CPP exhibited significantly higher fluorescence compared to cells incubated with fluoPNA alone or CPP alone (Fig. 2). This further demonstrated the high efficiency of CPP as a fluoPNA carrier. Compared with the control, simultaneous addition of PNA and CPP resulted in a significant increase in fluorescence in both the HEK293T (276 ± 7 vs. 540 ± 158; p < 0.01) and HeLa (212 ± 34 vs. 638 ± 70; p < 0.01) cell lines. These results underscore the potential of CPPs for delivering fluoPNAs into cells to modulate gene expression or other cellular processes.

Western Blot Analysis

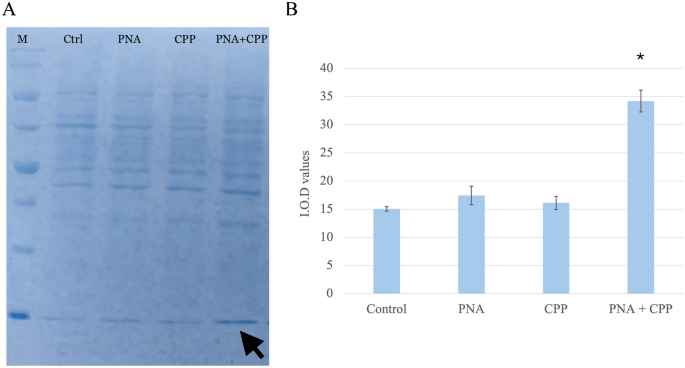

To estimate the relative level of fluoPNA in the cells, Western blot analysis was performed followed by staining of the PVDF membrane with Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye. In samples derived from HeLa cells treated with both CPP and fluoPNA, a stronger band intensity was observed after staining than in the other samples, as visualized on the membrane (Fig. 3). The integrated optical density (IOD) value was measured for all the samples using Fiji software. The lowest IOD value was observed in the control sample (i.e., in cells incubated solely with PNA), whereas the sample containing both CPP and fluoPNA exhibited the highest IOD value. Therefore, quantitative analysis of the Western blot data confirmed the enhancement of the cellular internalization of fluoPNA in the presence of CPP. The differences observed in signal intensity were statistically relevant (p < 0.01).

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

The samples prepared for Western blot analysis were later analyzed using HPLC. The chromatograms displayed distinct peaks, suggesting that the reaction mixture was free of byproducts or additional compounds. The retention time (RT) was 3.5 min. The area under each peak was calculated for all samples using D-7000 HSM software version 4.1 to quantify the total amount of fluoPNA molecules. Each reaction mixture was analyzed in triplicate, with three injections of 15 µL. The results of the HPLC analysis corroborated the Western blot results, ultimately confirming that CPP facilitates the transport of fluoPNA across the cell membrane, thus enabling its efficient penetration into the cells (Fig. 4).

MTT Assay

MTT-based cell viability analysis demonstrated that the tested compounds, as well as their combination, did not exhibit significant cytotoxic effects at the applied concentrations. The average cell viability in all treated groups was higher than 100% relative to the control. The viability of cell lines treated with PNA, CPP, or their combination (PNA + CPP) was comparable to that of the negative control group.

In the case of HEK293T cells, the highest viability was observed in the group treated with PNA (121.33%), suggesting a possible cytostimulatory effect (either proliferative or metabolic). The PNA + CPP group also showed increased viability (114%), while treatment with CPP alone (102.67%) did not differ significantly from the control.

For the HeLa cell line, no cytotoxic effects were observed either; the average viability under all conditions exceeded 100%. Statistically significant increases in viability were found in samples treated with PNA alone (108.76%) and CPP alone (107.73%) compared to the control.

Importantly, the group treated with the combination of PNA + CPP (101.03%) showed viability comparable to the control. This statistically significant reduction of the stimulatory effect in the combination compared to PNA alone (p < 0.05) suggests that their interaction in solution or during internalization negates the potential cytostimulatory effect observed for the individual compounds.

The results of the cytotoxicity assay showed that the tested compounds exhibit a very high safety profile with respect to cellular toxicity.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate the effectiveness of cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) in cotransporting gene-specific peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) into cells. We utilized cell culture experiments, Western blot analysis, fluorescence measurements, and HPLC to demonstrate that the co-administration of CPPs with fluoPNA—but not fluoPNA alone—improved its delivery into HEK293T and HeLa cells in vitro. These results remain consistent with those published previously (Turner et al. 2005). We confirmed that in our experimental settings, peptide nucleic acid oligomers can successfully pass through cell membranes, reaching the cytoplasm. Thus, a covalent binding between fluoPNA and CPP is not mandatory.

Our general research project involved the utility of fluoPNA in inhibiting the expression of genes from hypercholesterolemia-related pathways. Therefore, all our experimental fluoPNA oligomers possess an NLS sequence attached at their C-terminus (Pro-Lys-Lys-Lys-Arg-Lys-Val-amide) to enable possible inhibitory interference with genomic DNA. The results obtained by fluorescence microscopy revealed that fluorescein-labeled fluoPNA was observed inside the cells and tended towards aggregation in a specific manner (Fig. 1). However, it remains to be confirmed whether the PNA reached its intended target or whether the observed accumulation was coincidental. Unfortunately, our experimental equipment did not allow us to achieve a deeper view of the analyzed cell lines and CPPs.

The use of CPPs opens new perspectives for the delivery of therapeutic molecules, such as PNA, to target cells, which may represent a breakthrough in targeted therapy. This study acknowledges that cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) exhibit limited selectivity towards various cell types, a characteristic documented in the initial stages of the experiment. Furthermore, cytotoxicity was observed when higher concentrations of CPPs were applied. These properties constitute significant limitations that must be considered in the design of CPP-based drug delivery systems. To minimize these undesirable effects, future research plans include optimizing the CPP structure and implementing targeted drug delivery strategies aimed at increasing selectivity and reducing cytotoxicity.

The success of our research was possibly due to the careful selection of PNAs and CPPs based on earlier analyses. Preliminary tests using cell-free transcription/translation systems allowed for the identification of PNAs with an optimal sequence and concentration, that target specific regions of the genome. In parallel, comparative in vitro analyses of various CPPs (Tat, TD2.2, TP10) were conducted to select the most effective carrier.

Despite Tat and TD2.2 being widely recognized as universal CPPs, our preliminary studies showed that TP10 had the highest efficiency for PNA transport (Wender et al. 2000). This surprising result can be explained by the unique properties of TP10. Its high ability to penetrate cell membranes results from optimally balanced amphipathicity, enabling effective interactions with the hydrophobic interior of the membrane and the hydrophilic cellular environment. The helical structure of TP10 ensures stability in the membrane, facilitating translocation. The positive charge of the TP10 molecule, resulting from its amino acid composition, further supports cell membrane permeability. Indeed, TP10 acts through direct interaction with the membrane, creating temporary pores, which distinguishes it from CPPs that act on the principle of endocytosis. This direct mechanism may be particularly effective in certain cell types. The combination of these features makes TP10 an exceptionally effective PNA carrier, as confirmed by our comprehensive analyses.

The study described in publication (Turner et al. 2005) demonstrated that PNA-CPP conjugates effectively inhibited Tat-dependent transactivation in cells. The results presented by the authors indicated that PNAs can be used as a potential antiviral drugs and that CPPs provide an effective tool for their delivery. This phenomenon was confirmed by our study, which provided further information that the use of PNA in conjunction with CPPs could be a promising strategy for delivering therapeutic molecules to their destination.

Another approach was presented by the authors in Cordier et al. (2014). They focused on developing and evaluating a method for the effective delivery of antisense PNAs into cells. The authors concentrated on utilizing CPP (R/W)9, which is rich in arginine and tryptophan residues, aiming to enhance cell membrane penetration efficiency. Researchers obtained results demonstrating that conjugation of PNA with CPP (R/W)9 significantly increased PNA internalization into cells compared to unconjugated PNAs. These conjugates effectively inhibited the expression of target genes, and the CPP itself exhibited low cytotoxicity to cells.

Our study demonstrated that the simultaneous addition of CPP with PNA (CPP TP10 and PNA with the sequence Fluo-PCSK9-PPT-EX1-Ahx-NLS) to the cells was sufficient for effective cellular PNA internalization. These data indicate that at least some CPPs can be combined with different PNA molecules, creating a universal research tool. After achieving the most satisfactory results, CPPs can be permanently linked to PNA, thus further improving the efficiency of intracellular transport.

Considering earlier research, including the pioneering work involving TP10 conjugates (Pooga et al. 1998; Fossat et al. 2010), researchers frequently utilized a covalent attachment strategy, often employing disulfide (-SS-) cleavable linkers to ensure cargo release upon reduction in the intracellular environment. However, current data demonstrating successful cellular internalization of PNA via simple co-incubation with the TP10 carrier thus highlight the potential of non-covalent complexation as a highly flexible and adaptable delivery strategy. While covalent conjugation represents a powerful, proved and high-efficiency method, indeed requires complex synthesis of each PNA target.

Our co-incubation method provides a straightforward, potentially universal research tool for rapid PNA sequence screening. Nevertheless, this designation warrants an important clarification, in line with the critique regarding complex characterization. The effectiveness and claimed ‘universality’ of the non-covalent CPP/PNA system are entirely dependent on the formation of stable nanoparticles mediated by electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, which are highly sensitive to the PNA both sequence and length. Therefore, the physical characteristics of the resulting non-covalent complexes are critical determinants for internalization efficiency and must be further characterized to precisely define the utility of this application.

The history of CPPs as highly effective and versatile vectors supports our current approach (Ruczynski et al. 2014). Indeed, the efficacy of TP10 as a carrier for nucleic acid analogues is well-established; for instance, Wierzbicki et al. (Wierzbicki et al. 2014) directly demonstrated the high efficiency of Transportan 10 in delivering siRNA into cells. This evidence strongly supports the use of TP10 for the non-covalent transport of PNA oligomers as well, focusing us to precise control and optimization of the non-covalent formulation parameters.

PNA which can silence ACLY expression might be useful in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia, which is a growing health concern affecting a significant portion of the global population. Currently available therapeutic strategies for hypercholesterolemia encompass numerous approaches, including, for example, lifestyle modifications and pharmacological interventions. In the latter case, there is a broad spectrum of drugs available, including statins, ezetimibe, fibrates, and PCSK9 inhibitors, including monoclonal antibodies and inclisiran.

Although the etiology of hypercholesterolemia is complex, certain genetic factors play a significant (pathological) role, particularly in hereditary hypercholesterolemia (Abifadel et al. 2003; Sobati et al. 2020). Genes such as PCSK9, APOB100, LDLR, GLP1R, ACLY, and others are involved in the pathogenesis of this disease, and serve as therapeutic targets for modern antiatherosclerotic drugs, including gene expression modulators (Shapiro et al. 2018). For example, inclisiran is an siRNA molecule directed against PCSK9. Besides siRNA, other molecules with antisense or antigene activity, such as phosphate derivatives, aptamers, and PNAs, are also being introduced into therapy (Abifadel et al. 2003). Peptide nucleic acid, due to its unique properties, may represent another promising treatment agent for this disease entity. Nevertheless, a limitation in their application is the difficulty in intracellular transport, resulting from their nonionic nature. To overcome this barrier, attempts have been made to introduce PNA into cells using electroporation, liposomes, or CPPs. The pursuit of this issue stems from our long-standing involvement in research on hypercholesterolemia and PNA. CPPs represent a promising strategy, as they can function as carriers in both covalent and non-covalent linkages.

Despite demonstrating high CPP efficacy in PNA transport, our study still has certain limitations that should be considered. A primary limitation was the choice of cell lines. Although a wide range of lines were tested, optimal results were obtained with the HeLa and HEK293T lines, which are commonly used in in vitro studies due to their high transfection efficiency. However, for a more comprehensive assessment of the therapeutic potential of the studied molecules, it would be advisable to expand the research toward more specific cell lines reflecting therapeutically important target cells or tissues. For example, in the context of metabolic diseases related to the PCSK9 gene, it would be purposeful to use hepatocytes or hepatocyte-derived cell line(s) as the liver plays a crucial role in cholesterol metabolism.

Future studies should consider drug delivery methods, formulations, bioavailability, distribution, and biological barriers. Expanding the research to include these elements will enhance the understanding of the therapeutic potential of CPP and PNA in metabolic disease treatment, providing a basis for developing new therapies that may improve patient quality of life.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

- Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabès J-P, Allard D, Ouguerram K, Devillers M, Cruaud C, Benjannet S, Wickham L, Erlich D, Derré A, Villéger L, Farnier M, Beucler I, Bruckert E, Chambaz J, Chanu B, Lecerf J-M, Luc G, Moulin P, Weissenbach J, Prat A, Krempf M, Junien C, Seidah NG, Boileau C (2003) Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet 34:154–156. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1161Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Berillo D, Yeskendir A, Zharkinbekov Z, Raziyeva K, Saparov A (2021) Peptide-based drug delivery systems. Medicina (Kaunas). https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57111209Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Bottens RA, Yamada T (2022) Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) as therapeutic and diagnostic agents for cancer. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14225546Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Cordier C, Boutimah F, Bourdeloux M, Dupuy F, Met E, Alberti P, Loll F, Chassaing G, Burlina F, Saison-Behmoaras TE (2014) Delivery of antisense peptide nucleic acids to cells by conjugation with small arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptide (R/W)9. PLoS ONE 9:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104999Article CAS Google Scholar

- Fossat P, Dobremez E, Bouali-Benazzouz R, Favereaux A, Bertrand SS, Kilk K, Léger C, Cazalets J-R, Langel U, Landry M, Nagy F (2010) Knockdown of L calcium channel subtypes: differential effects in neuropathic pain. J Neurosci 30:1073–1085. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3145-09.2010Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Gori A, Lodigiani G, Colombarolli SG, Bergamaschi G, Vitali A (2023) Cell penetrating peptides: classification, mechanisms, methods of study, and applications. ChemMedChem 18:e202300236. https://doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.202300236Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Gupta A, Mishra A, Puri N (2017) Peptide nucleic acids: advanced tools for biomedical applications. J Biotechnol 259:148–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.07.026Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Hajar R (2019) PCSK 9 inhibitors: a short history and a new era of lipid-lowering therapy. Heart Views 20:74–75. https://doi.org/10.4103/HEARTVIEWS.HEARTVIEWS_59_19Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Katzmann JL, Gouni-Berthold I, Laufs U (2020) PCSK9 inhibition: insights from clinical trials and future prospects. Front Physiol 11:595819. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.595819Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Lee JH, Shores KL, Breithaupt JJ, Lee CS, Fodera DM, Kwon JB, Ettyreddy AR, Myers KM, Evison BJ, Suchowerska AK, Gersbach CA, Leong KW, Truskey GA (2023) PCSK9 activation promotes early atherosclerosis in a vascular microphysiological system. APL Bioeng 7:046103. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0167440Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Lehto T, Ezzat K, Wood MJA, Andaloussi SE (2016) Peptides for nucleic acid delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 106:172–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2016.06.008Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Liu C, Chen J, Chen H, Zhang T, He D, Luo Q, Chi J, Hong Z, Liao Y, Zhang S, Wu Q, Cen H, Chen G, Li J, Wang L (2022) Pcsk9 inhibition: from current advances to evolving future. Cells. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11192972Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Machnik G, Labuzek K, Skudrzyk E, Rekowski P, Ruczyński J, Wojciechowska M, Mucha P, Giri S, Okopień B (2014) A peptide nucleic acid (PNA)-mediated polymerase chain reaction clamping allows the selective inhibition of the ERVWE1 gene amplification. Mol Cell Probes. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcp.2014.04.003Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Montazersaheb S, Hejazi MS, Nozad Charoudeh H (2018) Potential of peptide nucleic acids in future therapeutic applications. Adv Pharm Bull 8:551–563. https://doi.org/10.15171/apb.2018.064Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Patel SG, Sayers EJ, He L, Narayan R, Williams TL, Mills EM, Allemann RK, Luk LYP, Jones AT, Tsai Y-H (2019) Cell-penetrating peptide sequence and modification dependent uptake and subcellular distribution of green florescent protein in different cell lines. Sci Rep 9:6298. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42456-8Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Pellestor F, Paulasova P (2004) The peptide nucleic acids (PNAs), powerful tools for molecular genetics and cytogenetics. Eur J Human Genet EJHG 12:694–700. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201226Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Peterson AS, Fong LG, Young SG (2008) PCSK9 function and physiology. J Lipid Res 49:1595–1599. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.cx00001-jlr200Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Polak A, Machnik G, Bułdak Ł, Ruczyński J, Prochera K, Bujak O, Mucha P, Rekowski P, Okopień B (2024) The application of peptide nucleic acids (PNA) in the inhibition of proprotein convertase Subtilisin/Kexin 9 (, jakarta.xml.bind.JAXBElement@718f970, ) gene expression in a cell-free transcription/translation system. Int J Mol Sci 25: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25031463

- Pooga M, Soomets U, Hällbrink M, Valkna A, Saar K, Rezaei K, Kahl U, Hao JX, Xu XJ, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Hökfelt T, Bartfai T, Langel U (1998) Cell penetrating PNA constructs regulate galanin receptor levels and modify pain transmission in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 16:857–861. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt0998-857Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Ramsey JD, Flynn NH (2015) Cell-penetrating peptides transport therapeutics into cells. Pharmacol Ther 154:78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.07.003Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Ruczynski J, Wierzbicki PM, Kogut-Wierzbicka M, Mucha P, Siedlecka-Kroplewska K, Rekowski P (2014) Cell-penetrating peptides as a promising tool for delivery of various molecules into the cells. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 52:257–269. https://doi.org/10.5603/FHC.a2014.0034Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Ruczyński J, Prochera K, Kaźmierczak N, Kosznik-Kwaśnicka K, Piechowicz L, Mucha P, Rekowski P (2024) New conjugates of vancomycin with cell-penetrating peptides-synthesis, antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity, and BBB permeability studies. Molecules. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29235519Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Ruseska I, Zimmer A (2023) Cellular uptake and trafficking of peptide-based drug delivery systems for miRNA. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 191:189–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2023.08.019Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Saarbach J, Sabale PM, Winssinger N (2019) Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) and its applications in chemical biology, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Curr Opin Chem Biol 52:112–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.06.006Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez J-Y, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9:676–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Seidah NG, Abifadel M, Prost S, Boileau C, Prat A (2017) The proprotein convertases in hypercholesterolemia and cardiovascular diseases: emphasis on proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9. Pharmacol Rev 69:33–52. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.116.012989Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Shapiro MD, Tavori H, Fazio S (2018) PCSK9: from basic science discoveries to clinical trials. Circ Res 122:1420–1438. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311227Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Singh T, Murthy ASN, Yang H-J, Im J (2018) Versatility of cell-penetrating peptides for intracellular delivery of siRNA. Drug Deliv 25:1996–2006. https://doi.org/10.1080/10717544.2018.1543366Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Sobati S, Shakouri A, Edalati M, Mohammadnejad D, Parvan R, Masoumi J, Abdolalizadeh J (2020) PCSK9: a key target for the treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Adv Pharm Bull 10:502–511. https://doi.org/10.34172/apb.2020.062Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Suparpprom C, Vilaivan T (2022) Perspectives on conformationally constrained peptide nucleic acid (PNA): insights into the structural design, properties and applications. RSC Chem Biol 3:648–697. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cb00017bArticle CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Turner JJ, Ivanova GD, Verbeure B, Williams D, Arzumanov AA, Abes S, Lebleu B, Gait MJ (2005) Cell-penetrating peptide conjugates of peptide nucleic acids (PNA) as inhibitors of HIV-1 Tat-dependent trans -activation in cells. Nucleic Acids Res 33:6837–6849. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki991Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Wender PA, Mitchell DJ, Pattabiraman K, Pelkey ET, Steinman L, Rothbard JB (2000) The design, synthesis, and evaluation of molecules that enable or enhance cellular uptake: peptoid molecular transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:13003–13008. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.24.13003Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Wierzbicki PM, Kogut-Wierzbicka M, Ruczynski J, Siedlecka-Kroplewska K, Kaszubowska L, Rybarczyk A, Alenowicz M, Rekowski P, Kmiec Z (2014) Protein and siRNA delivery by transportan and transportan 10 into colorectal cancer cell lines. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 52:270–280. https://doi.org/10.5603/FHC.a2014.0035Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Yurtseven E, Ural D, Baysal K, Tokgözoğlu L (2020) An update on the role of PCSK9 in atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb 27:909–918. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.55400Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Internal Medicine and Clinical Pharmacology, Faculty of Medical Science in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, Medykow 18, 40-752, Katowice, PolandAgnieszka Polak, Grzegorz Machnik, Łukasz Bułdak, Weronika Wójtowicz & Bogusław Okopień

- Laboratory of Chemistry of Biologically Active Compounds, Faculty of Chemistry, University of Gdańsk, Wita Stwosza 63, 80-308, Gdańsk, PolandJarosław Ruczyński, Katarzyna Prochera, Piotr Mucha & Piotr Rekowski

Contributions

Study design: G.M., A.P. and Ł.B.; data collection: A.P., G.M. and J.R.; data interpretation: G.M., A.P. and Ł.B.; manuscript preparation: G.M., A.P. and W.W.; figures preparation: A.P. and W.W.; literature search: G.M., A.P.; PNA synthesis: J.R., K.P., P.M., P.R.; funds collection: G.M., A.P., J.R., and K.P. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

**Disclaimer:** This article is intended for informational and educational purposes only. The content presented is a summary of existing scientific research and does not constitute medical or health advice. Ipamorelin is a research chemical and has not been approved by the FDA or other regulatory bodies for the diagnosis, treatment, cure, or prevention of any disease or condition. It is not intended for human consumption.

Is this article making health claims?

No. This article explicitly does not make any health or therapeutic claims. It is a summary of existing scientific research presented for informational and educational purposes only. The disclaimer at the beginning of the article is a critical part of this communication.

AOD-9604 5mg

AOD-9604 5mg